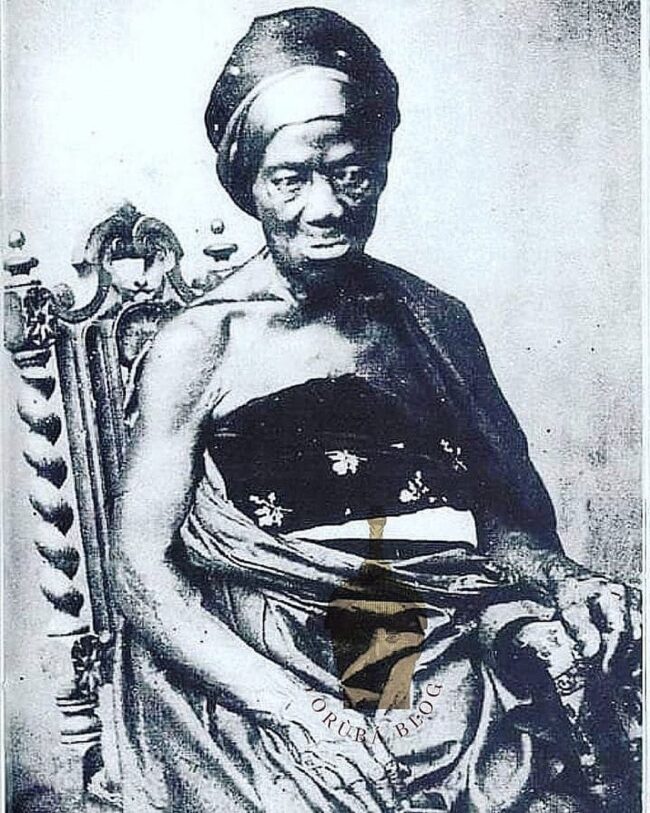

Aláafin Abiodun Adegorolu was the successor to Aláafin Ajabo, a strong monarch at the time. A girl named Osu was born to Aláafin Abiodun. She grew up to become the mother of Olámínigbin, who married Omo-oga-egun. Together, they had a child named Ibisomi Telerinmasa. As the princess or priestess of the great god Obatala (the god of white cloth), Telerinmasa was said to possess a unique dignity that was recognized by her people as “Afala” (the one who loves purity or the pure one). It is said that the province of Obatálá is a domain of perfect and brilliant purity. Afala wed an Edu clan member whose name was also given as Ajayi; his grandfather was the Baale of Awaiye-petu, who moved from Ketou Dahomey (now in the Benin Republic) to the Oyó empire. After the Fulani slave traders invaded their town, Oshogun, near Isheyin, in approximately 1821, Afala parted ways with her handsome son when he was just 12 years old. As a devoted mother, she eagerly anticipated the day she would undoubtedly see her son once more. Slavery had kept them apart for decades, but during Ajàyi’s missionary journey in Abéökúta, they were eventually reunited. On February 5, 1848, in Abeokuta, Madam Afala was given the name Hannah and subsequently baptized by her own son. In Abeokuta, Madam Hannah and a few other family members moved in with the bishop, where she lived to be over a century old.