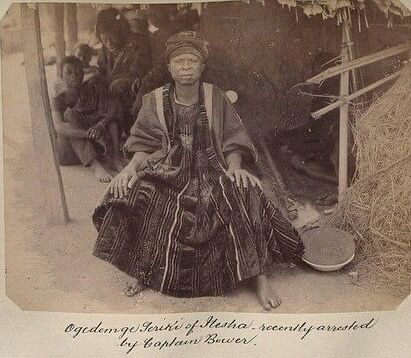

Biography of Ogedengbe Agbogungboro, Leader of Ilesa and Seriki (Commander-in-Chief) of the Ekiti-Parapo Warriors

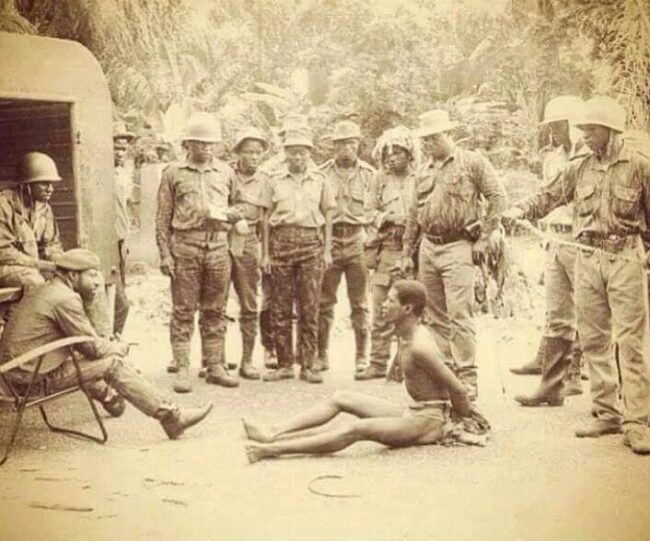

A warlord and leader of Ilesa, Ogedengbe Agbogungboro was born in 1822 and died on July 29, 1910. He was also the Seriki (commander-in-chief) of the Ekiti-Parapo warriors during the Kiriji War (1877–1893) against Ibadan. British involvement: He was taken prisoner in 1864 while protecting Ilara-Mokin from Ibadan. After being trained by Bada Aki-Iko, an Ibadan warrior, he managed to flee. During the 1867 Igbajo War, he was caught once more but managed to get away.He received military strategy training from these two events. He became a hero after Ogedengbe led his troops to expel Odole Ariysasunle, an Ijesa chief, from Ilesha after he reportedly gave Ibadan military secrets. Ogedengbe attacked Idoani in 1878. After losing a number of his soldiers in the battle, he was only able to defeat Idoani and retreat to Itaogbolu later in 1879. The Ekiti-Parapo confederacy’s army was established in 1878 to spearhead an assault on Ibadan following the outbreak of the Kiriji War. After relocating to the town of Igbara-oke, Ogendengbe organized a journey to the Kingdom of Benin in 1878. Despite his initial hesitancy, Ogedengbe canceled his journey to the Kingdom of Benin to head the army at the request of war chiefs.Ogedengbe was met with applause and ovations upon his arrival at the base, and Prince Fabunmi willingly resigned in his place. In the midst of the conflict, he assisted in freeing the territories of northeastern Yoruba from Ibadan’s rule. Following the 1886 accord, he and his soldiers withdrew to Imesi village until 1893, when Ibadan and Ilorin clashed. Captain Robert Lister Bower of the British Army, the Resident of Ibadan and the political officer of Lagos Colony, issued a warning after his group of fighters took part in the raid on nearby fields and inhabitants. Ogedengbe was detained and imprisoned in Ibadan by Captain Bower in 1894. He was sent to Iwo when the Ilesha authorities objected to the place where he was being held. Following lengthy discussions, Ogedengbe was released by Gilbert Thomas Carter, the British colonial governor of Lagos Colony, after Fredrick Kúmókụn Adédeji Haastrup, the Owa of Ilesa, paid a fine of 6,000 British pounds. After Ogedengbe repeatedly turned down the opportunity to become Owa Obokun, or king, of Ilesha, he was given the chieftaincy title Obanla or Obala, which translates to “Mighty King,” in 1898 in recognition of his actions during the Kiriji War. He passed away on July 29, 1910, when he was approximately 88 years old.